Hypermobility and the female CrossFitter

Today I have teamed up with Joy Victoria (From Fitness Baddies) and we’re bringing you a question and answer style post about hypermobile female CrossFitters and the issues they face. Joy is extremely experienced, having worked with many women who have these issues (as well working on herself over the years), so I was super excited to pick her brain! I sent her a list of questions, and what I received back is a gold mine! If you are a hypermobile female, a coach or trainer, or train with someone who is, I can’t tell you enough how valuable this information is. It’s a bit long and will probably take some focus and effort to digest it all, but it’s so worth the read!

I thought I would start things off with a background story behind this post. As a trainer and CrossFit coach, I am constantly presented with hypermobile women of all ages. This is so much more common in females than in men. I have been quite concerned about this for some time now, and especially the fact it is something I rarely see coaches or individuals addressing but it is one of the major causing factors of chronic injuries in athletes. Hypermobility or joint laxity can cause problems if the coach or athlete is not aware of one’s body, movement patterns, and any compromised positions they may be getting into.

The deceiving thing about hypermobility in CrossFit is; it is often disguised as “good form”, and athletes who present with this condition are encouraged to continue doing so. They can be seen as “perfect examples” of form, even though putting their bodies in these positions may be compromising their stability and causing injuries/nagging issues.

Sayings like “ass to grass depth”, “great lock out” “bounce out of the squat” etc get thrown around like they are the holy grail of being a good CrossFitter. I believe this is because CrossFit (as a methodology/sport) has very stringent policies on what constitutes proper form or “a rep”…i.e. arms locked out overhead, hips open, squat below parallel etc. It’s often “all or nothing” with the CrossFit form- police. Bodybuilding-type training methods, like partial reps, tempo reps, iso holds, etc don't have much of a place in CrossFit training (but would more than likely be extremely beneficial for hypermobile people to add into their training.)

Following are my questions (posed as a hypermobile female CrossFitter), and Joy’s replies. Later down in the post she discusses strengthening and stability drills and we have done video demos for everything which we have posted as well.

1.) How do I know if I am hypermobile?

Figuring out if you are hypermobile is pretty easy. You can do a simple test on your joints that will give you a good idea if you are prone to hypermobility. Follow along below with this excerpt from my blogpost “Are you Gumby? Joint Laxity and What’s Bad About too Much Flexibility”:

“Follow along the numbered list and watch this accompanying video about Testing for Congentital Laxity and Hypermobility, and you can get a better visual of what hypermobility looks like.

* 1 Flexion of the thumb to the forearm to make contact (L + R sides)

* 2 Extension of the pinky finger to 90° past the hand (L + R sides)

* 3 Hyperextension of the elbow past 10° or more (past neutral)

* 4 Ability to touch palms to floor without bending of the knees

* 5 Hyperextension of the knees past 10° or more

Beighton Score (Picture credit: www.foothealth4kids.com.au)

Beighton Score (Picture credit: www.foothealth4kids.com.au)

The video showed the quick tests to determine if you are hypermobile in certain joints. This is called the Beighton Laxity Test, and it is scored out of a possible scale of 9. A score of 5/9 is considered hypermobility.”

Note: Joint hypermobility can be one symptom of other more serious genetic conditions, including Ehlers-Danlos and Marfan Syndrome. It’s a good idea to rule out any of these conditions if you find yourself repetitively injured, prone to joint trauma or have other physical symptoms you are unsure of beyond hypermobility. They are more rare, of course, but important to know about. If diagnosed, Crossfit is not the exercise methodology for you. Inappropriate intensity in exercise can result in significant trauma and pain over time. Exercising and lifting can benefit everyone, but it must be done in a way that is right for your body and needs.

Even if you are not significantly hypermobile, the following information is valuable to anyone, especially for females, who struggle with motor control, exercise technique and/or chronic joint problems in exercise.

Particularly, SI joint or low back pain, neck tightness, knee pain and poor core strength. I hear of issues too often from other girls in training, that discourages them from lifting. This article can help.

As Libby mentioned, women in general have more laxity (looseness) in their joints in general. Our hormonal fluctuations during menstruation and pregnancy affect this too. Women need to work harder, relative to men, to develop muscle and muscular stability. They may need more time building up to harder and more technical movements and heavier lifts, as well as more time building muscle to support said movements.

Note: All of the recommendations and answers below are under the context of hypermobility, and may or may not be entirely applicable in other contexts.

2.) How does being hypermobile affect someone in their strength training, learning exercises or improving their technique?

There are several important things to be aware of, if you test as hypermobile. All of the points below are referenced from the research paper, “When flexibility is not necessarily a virtue: a review of hypermobility syndromes and chronic or recurrent musculoskeletal pain in children” (1)

While the title of the paper says “children”, these principles are the same for adults, in regards to training.

1.) “Other factors may contribute to the development of the (BJHS) syndrome, such as poor proprioception, autonomic dysfunctions and fatigue secondary to poor sleep.”

What this means:

* - Showing up for a workout tired means you have less control of your limbs, less awareness of your body in space (proprioception) and less ability to control your movements.

* - Proprioception is “body awareness”. A mental image of where your body is in space. Imagine an elite gymnast, or a top rugby player. Watch them move. They will show you “great body awareness”. It’s impossible to do complex, fast and technical movements without good “body awareness” or proprioception. Fatigue directly impacts this ability, and can make the process of working out much more risky, and or frustrating. Being aware of your sleep habits, may not seem directly important to “learning to do a handstand pushup”, but it actually is. Why? Tiredness reduces your proprioception, your body’s ability to learn, and your ability to focus. This will directly increase your risk of injury. Why? Because your body cares about not getting hurt! Even though consciously you might feel “ok”, research proves that those who are chronically tired over time, fail to notice the deficits in their energy and performance and can suffer effects you might not have tied into your sleep at all. You won’t even be able to recognize how tired you are, until to get out of the familiar shitty sleep cycle.

* - Not training in a chronically fatigued state (how many nights this week did you get to bed late? How many hours of sleep do you get on average?) is of importance to everyone, but for those with hypermobility or poor body awareness, it is of SUPREME importance. This doesn’t mean that if you skip a night of sleep, you need to freak out, but it does mean that skipping or cutting sleep short regularly, is a serious issue.

* - Additionally, if you are an early morning exerciser, you need to take time for a more thorough warm-up. According to spine researcher Stuart McGill, your back is more at risk in the morning due to fluid buildup in the discs. You want to avoid any exercises that include deep flexion (good mornings, GHR situps, kettlebell swings etc). If you are an early morning exerciser, you need to schedule time for a proper warmup and avoid heavy flexion exercises first thing.

2.) “The management of individuals with BJHS (benign aka non-life threatening or medically serious joint hypermobility syndrome) can be very challenging and there are no evidence-based management strategies currently available. Acute pain episodes are commonly managed using taping, bracing or splinting or with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as needed. However, reassurance and a multi-disciplinary training program are the mainstays of long term management. Physical therapy is of the utmost importance, and encouraging an active lifestyle may improve function and enhance quality of life.”

What this means:

- The last two sentences are most important. Taping, knee sleeves, wrist supports, massage therapy, even belts (in place of time spent strengthening the core, NOT because belts are bad or useless) foam rolling etc are only temporary solutions. They can complement your training wonderfully, but they do not replace the need for increasing body awareness and learning muscular or active control in your exercises and lifts. No supporting tool will replace the time you spend actively learning to move well.

* - A hypermobile person may have to work much harder at understanding what muscular control feels like, and use strategies in their exercises and lifting that respect that (more on that below).

* - Your joints are at risk, automatically. You must protect them. There is no way around this, and buying straps, sleeves and belts won’t fix that. If you can easily drop down into a squat, but cannot maintain muscular control of your “squat” while you do it, than you are “hanging out on your joints”, as I call it. The good news is that, with proper training, and progression you can train every exercise and physical quality that you like.

* - Moves that are more technical (muscle-ups, Olympic lifts, pistol squats, etc), and/or fast and powerful (sprints, Olympic lifts, kettlebell swings) need to be trained appropriately, instructed properly, and may take longer to build up to. While this might not be good news to some, the alternative could be chronic joint pain, injury and or the inability to continue in the training of your choice; Crossfit.

3.) Why do I always feel tight? Should I stretch?

What is tight?

The feeling of tightness is usually complained about in terms of range of motion. So, someone who can’t touch their toes, will complain of “tight hamstrings”, and want to stretch their hamstrings in order to increase their range of motion; get closer to their toes.

The opposite of tight is loose. So we think “stretching will make me “looser” and relieve tightness”.

Tightness can also feel more general, as in chronic neck or hip tightness. This can develop from exercising in a way that your body is not appropriately prepared for, even if you think you are doing it with good form.

While this seems to make sense, it’s not the whole picture.

Form is both positioning (“good form”) and muscular control of positioning (good technique). How a muscle contracts and relaxes, or remains chronically “tight/short” or “unactivated/weak” depends on your nervous system, not on the muscle itself. A muscle acts on signals. You have two nervous systems; peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system. They communicate with each other to “tell” the muscles what to do. The CNS is your brain and spinal cord, the PNS is the nervous system that consists of the nerves and ganglia outside of the brain and spinal cord. So imagine what “your feet feel” = PNS (no squishy shoes while lifting, is an example of why this is important), communicates to your CNS about your overall balance, which in turn affects “how” you lift the weight with your muscles. So simply stretching in a certain position does not necessarily affect how your muscles “feel” in working out.

There’s also two basic types of stretching. Passive or static and active or dynamic. Imagine a ballerina holding her leg up without help in the air (active range of motion) vs propping it up on a wall and leaning over (passive/static).

Passive stretching is usually what people turn to, to solve “tightness”, but in the case of hypermobility, it can exacerbate the issues, as well as delay development in training by not addressing stability or motor control. And can merely increase joint looseness! So, contraindicated.

For more on the differences in stretching, and why this is important, check out: 15 static stretching mistakes

Stretching is not bad per se, but it’s important to understand why and how a certain way of stretching may not be right for you. Many athletes stretch regularly, but they have several other factors going for them, that an average hypermobile trainee may not, including

1.) A history of athletic training from a young age

2.) Active control of extreme ranges of motion through consistent training

3.) A good understanding of what is “right” and “wrong” for their body.

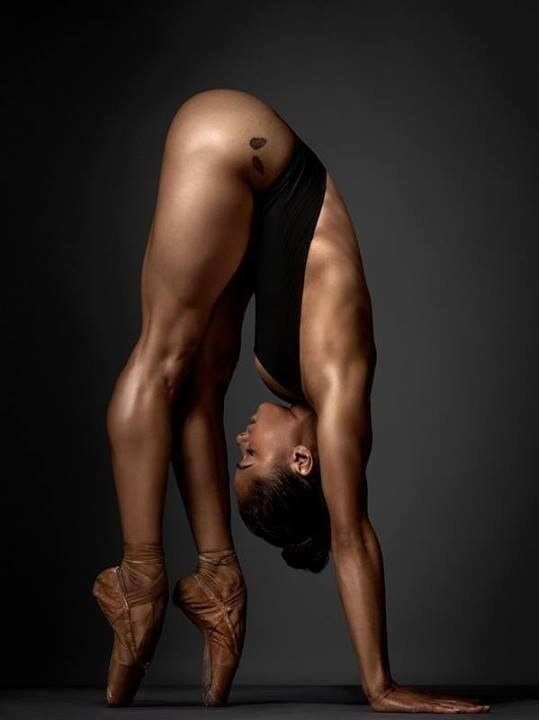

Athletes in sports that require extreme ranges of motion, such as gymnastics and ballet, train both extreme flexibility AND extreme control. Having the range of motion is one thing. Having STRENGTH in that range of motion is another. The first is potentially useless. But everyone can build the second!

Hypermobility is a seeming contradiction, but the clue is in the “hyper”. Too much flexibility without strength is dangerous to training.

Dancers require great flexibility AND great strength. It's a fine balance.

Dancers require great flexibility AND great strength. It's a fine balance.

(Picture credit: Henry Leutwyler Photography)

Joints and muscles work together in complex relationships that require certain muscles to stabilize, so others can move and vice versa. Often issues of tightness are a result of a backwards relationship between your “stabilizers” and your “movers”. An easy way to visualize this is your low back rounding or arching in movement, as opposed to your hips flexing and extending from well-activated glutes! The core is meant to “stabilize” your back so your hips can move, but instead if it is doing a lot of the “moving”, you can run into problems and overuse injuries in the low back and SI joint.

It is much harder to unlearn a bad pattern, than to learn a good one from the start. That’s why patience is important, especially for the loosey gooseys.

Working on stability in exercises and building strength gradually in bigger ranges of motion is the answer for relieving uncomfortable and chronic tightness.

At the end of this article, will be practical recommendations for your everyday training to put these concepts to work for you.

4.) My back and core often feels unstable in overhead lifting. I can get into the position by arching my back, but this doesn't feel good. Will a belt help? How can I understand how to position my back better?

First let’s understand how to think of our core. The core is your torso. It is all the muscles that support the trunk of the body, and includes the diaphragm, abdominal muscles, spinal erectors, deep spine muscles and pelvic floor muscles.

The core works as a pressure system. Appropriate pressure (not just holding your breath and turning blue) sends the movement to hips/shoulders, and loads the spine in a good way.

This is why belts are very useful in lifting. But they do not train core strength. Nor will they train the core to support the spine in movements.

Here are two visualizations to help you understand how the core works.

Imagine your ribcage as a bell. Arching the back “rings” the bell up. Hunching or slouching the shoulders, “rings” the bell back. Now imagine a ringing bell. Back and forth, back and forth. This is what many do in response to the cue “straighten your back” or “push your chest out” vs “get your abs back in” and “don’t stick your belly out”.

(Picture credit: www.jtsstrength.com)

But what is happening here is you are “ringing the bell” and creating movement or sheer in the spine and ribs. You want to keep the bell silent and still over your hips, and learn to create movement with the shoulders and hips. This takes time and has to be learned.

Another visualization is; your core is a beer can. The front/sides/back are your abdominal muscles, low back muscles (spinal erectors). The top is your diaphragm under your ribs. The bottom is your pelvic floor (the muscles of your vagina and anus, or “stop the pee” muscles).

You do not want any part of your “beer can” dented or collapsing. You want even pressure, and then integrating that “stability” into bigger movements.

The idea that just squatting and deadlifting “train the core” enough, is not correct. Your core works during those movements (as it will in any movement) and loading the torso and back, trains the torso and back, but that is all dependent on HOW good your movement is to begin with.

Either way, you will not find any top coaches who say that core and abdominal work is useless. In fact, it can be doubly important to train the core frequently and appropriately. I won’t go into the specifics of what that means here, just keep in mind that just doing the big lifts will certainly not be enough.

Overhead pressing requires a lot of shoulder mobility and upper body strength along with core stability. When this is lacking, you may arch the back in order to get the weight overhead.

Women need to work on building up upper body strength much more than men do, and shying away from this in fear of “getting too large” will negatively affect your training in Crossfit. If you prefer to not train Crossfit, than I suggest another style of training that does not require upper body strength. Like just sitting on an ab machine...or something. ;)

Either way, I find that those fears are largely unrealized once training begins. And if you are genetically gifted for muscle, DON’T YOU DARE BITCH ABOUT IT!

Focusing on lowering the weight, and relearning how to press WITHOUT arching the back is the fix for this.

You need to practice the new feeling of NOT arching the back to press overhead. You cannot do this using weight that is very challenging for you, as your “arch the back pattern” will take over.

Additionally, prioritizing basic bodybuilding hypertrophy exercises for the upper body is just a good idea! To keep the back “stable” in pressing, think of keeping the “bell” down, and pushing through the hands. If your posture is a significant issue (belly forward, shoulder rounded, or back arched), than isometric exercises in a correct position are a good bet (again, more on this at the end).

Pressing also requires the use of your hips, since your hips are your base. That is what’s under your “bell”. Keeping your hips under you, means you can use them to press.

If you are not sure what it feels like to use the hips (clue: its not just locking the knees), do your pressing from a kneeling stance, while keeping your glutes squeezed. Notice the difference.

Now try to replicate that standing. If you find it impossible to do so, lighten the weight, and practice pressing with dumbbells from your knees until you can change the feeling in your body.

This will increase your pressing strength and help you relearn a good pattern.

5.) When I do squats, wall balls, drop under heavy cleans, etc., I feel like I have no middle-ground in my squats. It’s either all the way up or all the way down. Are there any ways I can train my squat to be stronger so I can have a bit more control over my squat depth?

That’s because your body does not know how to absorb force in a stable position. Essentially what happens is you are “catching the weight” by collapsing down and then having to bounce out, because there’s no other way to come up.

Here we can visualize a rubber band. Can you shoot (power) a rubber band without stretching it first (eccentric component of exercise)? No. Without no stretch, there is no pop. But the key here is; what kind of stretch? The muscle kind! Not the “drop into my joints” kind!

Have you heard the term: “When an unstoppable force meets an immovable object?” What’s happening when you collapse under, is you are not “meeting” the weight. Therefore, you cannot control it. The weight ends up “controlling” you.

Do this drill to understand the concept of “meeting the weight” or absorbing the weight with a strong/muscular position as opposed to a floppy bouncey one:

1.) Get into a 1/2 squat. Shift your weight to your hips, keep your feet flat, knees in line with toes feet firm. Your basic good squat stance.

2.) Try to flex your butt and thighs without shifting your position.

> If you can do it, than grab a wall ball or barbell and practice stopping the movement there. Lighten the weight enough to be able to do this repetitively.

> If you can’t, than you need to build up some muscular endurance in that position or your legs, hips and core won’t “absorb” the impact of the weight and you will be pushed down.

Wall-sits or isometric squats with a band around your knees till your muscles burn (mechanical tension), are very useful to replicate this feeling. Then practice that with pause squats to build the strength.

For catching overhead lifts such as dumbbell snatches, snatches, kettlebell snatches etc, you can apply the same concept, but without the explosiveness.

> Hold a moderately heavy weight for you and hold it overhead, and practice getting used to a solid back position. Think of rooting yourself into the ground, feet firm, knees slightly bent and tension in the thighs and glutes. Don’t move. Don’t wobble. If you do…..you need to practice this.

> Single arm overhead walks with a dumbbell or kettlebell are great practice for this as well, once you get the right feeling.

The feeling you want to get is one of solidness and connection into the ground. You are the “pillar” on which the weight “lands”.

6.) Kipping?

Though I hate to say it, kipping is just not a good idea for hypermobile individuals, and there’s really no way around it. You need to build up the capacity to do a strict pull-up well with a stable back and shoulders, before even considering kipping.

Ideally you should do multiple strict pull-ups (8-10 minimum) well. Kipping induces enormous eccentric stress on the shoulder girdle, and there is no safe way to do it until you build up to it.

In the event that you want to ignore this, use a thick stretchy band that allows you to learn the rhythm and pattern EASILY. Even then, I do not recommend this.

7.) What if I am not hypermobile everywhere, but I have an exaggerated arch/lordosis in my lower back? Would the same principles apply to me?

Yes they would. These are basic concepts of muscular tension and movement that apply to anyone. But, hypermobile individuals are much more at risk.

If anterior pelvic tilt is the main concern, than learning how to reposition your hips under you and strengthening the glutes and lower abs will help. A lot of the drills at the end can be used for this as well, not just those with hypermobility.

BUT, you then you need to transfer the “feeling” you get in those drills over to your main lifts, and pay attention to doing so! Doing drills is one thing, but if the goal is better lifting and better movement overall, you need to take those concepts into your WOD when you are under heavier load, more speed etc. Otherwise you are wasting your time.

Good movement, is good movement. It just might take a bit more work and patience for you to build muscle and strength. But consider the alternative....not being able to train because of injury? An injured athlete can’t do athlete things.

The important thing to remember is that; it’s not how much you lift, but how you lift it. No matter who you are.

You can’t change your genetic code. But you can change how you train and how well you focus. Don’t stress about the cards you were dealt physically. Just play them right.

8.) What are some good and easy stabilisation drills and exercises I can include in my warm-ups or extra training time, so that I can still do the WODs and CrossFit workouts but make sure I am focusing on stability?

Here are my top stability exercises for hypermobile individuals, that focus on learning what muscular tension, and body control FEELS like:

Lower Body:

--Single Leg Balance - this strengthens the small muscles of the feet, improves proprioception and teaches stability. Stand on one leg. Do not lock the knee aggressively, stay in the middle of your foot and contract the glute, lift one leg, and hold. You will shake and wobble. That’s ok. Hold on to something at first. (Progression: move lifted leg out and in at the knee (standing clamshell) > close your eyes while holding > close your eyes while holding and moving out and in.)

--Innie/outie isometrics holds - if you don’t have an innie/outie machine, use a yoga block, small squish ball or dumbbell between your knees and a band around your knees.Progression: seated abduction with a band > change the back angle to hit glute med (stay straight) and glute max (lean forward).

--Front, Back and Lateral Monster walks with a band. Monster walks are stiff and robotic with muscle tension, not fluid and loosey goosey, where you glide across the floor. (Progression: get lower!)

--Isometric bilateral (two legged) wall squats with band around knees. Hold till your thighs burn, actively pushing out against the band. Then hold for at least 10 more seconds. (Progression: paused goblet squats)

--Isometric reverse lunge. Load the front hip, lean forward slightly. Keep your hips under you. This should be felt in the front hamstring and glute. Keep the knee over the middle of the foot, but no further. Actively push the floor away with the foot. (Progression: Isometic bulgarian split squat, split squats.)

Upper Body:

--Kettlebell Armbars - use a decently heavy weight for you. 12kg+. (Progression: 1/2 Getups)

--Overhead kettlebell or dumbbell holds for time till you feel stable - use a weight that you can press up, but only with some difficulty (so “a bit too heavy”). Use your other hand to help get it up. Keep the knees soft, settle into your feet. Stay still. (Progression: Overhead walks)

--Bicep curl band isometrics - use a mirror to help you get the right position for your shoulders. Your biceps should “pop”, and arms tremble when you get it right.

--Crawling - valuable exercise for everyone for shoulder mobility and stability. Tip: put a small weight plate or yoga block on your low back. Don’t let it fall as you crawl. This will automatically “force” you into doing it correctly.

--Bear Hold Isometric Tip: keep the knees close to your hands, and keep the knees out, actively “flexing” (not arching!) the bum. Big bum, big chest. Look up! This is also a great core exercise.

Core:

--Crocodile belly breathing - remember how I said the pelvic floor is the “bottom” of your core. This will help you learn how to tie in the top, the sides AND the bottom. If you have the habit of arching the ribs, this is what you need to practice. (Progression: Breathing dumbbell pullovers)

--Happy baby inner thigh squeeze - get a small squishy ball, or a yoga block, lay on your back, and bring the knees up over your belly. Squeeze the ball till your legs shake, while maintaining nose breathing. Pay attention to your ribs and low back. Ribs should stay down, and back should remain on the floor. (Progression: Squish the ball toe taps, with no back arch.)

--Yoga ball wall stir the pots - a variation of this popular exercise, but modified. Put the ball on the wall! Maintain a plank position with the body. Slow stirring, or just hold. (Progression: Regular stir the pots)

--1/2 Kneeling pallof press isometric Tip: squeeze the inner thighs to help with balance. The weight of your body stays over the BACK hip. Test this by trying to “lift” the front foot temporarily. If you fall over, reset over your back hip and squeeze the glute!

--Happy baby rolling and rolling - while this might not seem like a core exercise, it is! It works the lateral lines of the body, and is a basic “movement competency” that trains core stability in the transverse plane. This is how babies first start to move, by learning to roll over and lift the head. It trains the DEEP core stabilizers, the ones we can’t “think of contracting.”

These are very simple exercises, with endless variety for progression. Some may think they are almost TOO easy, but when done properly induce sweating, shaking and muscular growth!!

These are very simple exercises, with endless variety for progression. Some may think they are almost TOO easy, but when done properly induce sweating, shaking and muscular growth!!

In my professional experience, those who are hypermobile often do not do traditional “core stability” exercises well for one reason; they require too much movement.

This is why you don’t see deadbugs, lots of plank variations or chops and twists here. Those are valuable, but only once muscular stability is FELT first, and trained first. Moving can often distract someone from learning how to hold a position well, and I find that isometric variations teach this much better, before a movement is added to the position.

For an easy pre-WOD routine or warm-up, pick one from each category, and work up to progression for at least 4-6 weeks. Then pick again.

If an exercise is too hard to get right, try another one, and revisit it later.

Clues to success:

If your limbs tremble and your muscles burn you are doing it right. You may even start to sweat. This is good. You may feel weak or shaky when you are doing it right. But you should not feel burning pain in a JOINT.

Balance, balance, balance. If you are losing your balance, you change the whole intent of the exercise. If holding onto something helps you do it with good form, do so, but the goal is to LEARN better balance eventually. Good movement begins with keeping your balance. This is especially true for single leg exercises.

If you can relax and don’t feel much of anything, chances are you are not creating tension. This is one instance, especially in isometrics where pain (muscle pain/burning!) IS gain.

VISUALIZE and actively think about contraction. Imagine you are a bodybuilder trying to make your muscle “pop”. Muscle contraction in this way is a voluntary command, and must be thought about. Just getting into a position and holding it, won’t cut it.

If using a weight for an exercise, stay in “touch” with it. Often the first thing I notice in clients is hands or feet going “slack”, and losing active connection with the weight, even though you are still “holding onto it”. This changes the sensations and signals being sent to the body (remember your PNS?) about what to contract. Stay in “touch” literally with your weight. Send your mind there. This is hard and requires focus and concentration (remember how I said it’s hard to train tired?)

9.) What about extra strengthening work/isolation work? Can this be beneficial to me to add in as extras?

It’s a good idea for hypermobile individuals to devote significant time to learning how to create muscular tension with weight that is manageable.

A basic bodybuilding routine with lower weights, higher reps and focus on impeccable form and tension is recommended.

The good news is that this should not be significantly fatiguing or impact other training, as long as it is balanced well. This is key, as fatigue does what? It makes it harder for your body to learn!

Reducing the frequency of high power/speed training, and complex WOD’s or lifts, while you build muscle is smart. It will pay off.

Muscle is your motor. Take time to build it, and it will take you far, and protect your joints. It will also allow you to “learn” your own body and movement, which in turn will make learning more complicated exercises easier and less confusing.

It will also make you a highly sexy motherfucker.

Remember that the principles of:

- Progressive overload (making an exercise harder through more time, weight, or technique progression)

- Time under tension (enough time creating tension in the muscle, not just “doing a movement”)

- Adequate rest and recovery

Are the cornerstones of any type of training.

This might require you to shift your focus for the time being and prioritize your style of training accordingly.

It will pay off, especially if you love Crossfit and your joints!

References:

1.) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4596461/#CR33

Join the other 10,000+ who get my best fitness, diet & mindset tips.

Comments